This month we’re sharing an academic paper written by Will Williams, a Ph.D. archeology student at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York city and alumnus of Montclair State University. In July 2022, he and other student and volunteer archaeologists, under the leadership of MSU’s Dr. Chris Matthews, conducted excavations at the Montclair History Center’s 108/110 Orange Road campus. The timing of Will’s paper couldn’t be better: we were just notified that the New Jersey Historic Trust has awarded the Montclair History Center the capital improvement grant that prompted this excavation! (The capital improvement grant will allow us to make our entire site more ADA accessible…much more to follow on that initiative…)

Will’s paper helps us better understand the history of our Orange Road campus – home to the Israel Crane House and Historic YWCA (which was moved to this site in 1964), the Clark House (containing the MHC offices, library and archives), the Nathaniel Crane House (gift shop, school room), and the farm which we host as part of the Montclair Community Farm Coalition.

We hope you will find his research and explanation of the process as interesting as we did!

People often wonder what mark they will leave on society. Most of us are not famous, and we’re likely not significant enough to be the topic of a book. It’s reasonable to assume previous generations felt similar. This story is about a few of those people. The protagonists are ordinary middle-class suburbanites with everyday lives, working a job we assume meant something to them. Unbeknownst to this story’s subjects, and probably surprisingly, they did leave a mark on society. Only it wasn’t as legible as some histories are.

The purpose of this article is two-fold. First, it intends to bring public awareness to another historical aspect of Montclair History Center’s (MHC) land. The MHC sits on what was a 300-acre tract of land – initially occupied by the Munsee Lenape – and later owned by Jasper Crane (1605-1681) in the 17th century. It is now the site of the Israel Crane, Clark, and Nathaniel Crane houses.[1] Missing from the public record is the history of the Rose’s, a family of florists who operated a greenhouse and floral business on the site of the Israel Crane House from about 1899 to the mid-1930s. Secondly, this article discusses the important anthropological subject of gender and equality for women in the early decades of the 20th century. The florist shop and greenhouse was a woman-owned business run by Alice G. Rose. Her business ownership resisted the domestic roles women were expected to follow.

In July of 2022, a team of student and volunteer archaeologists continued exploring the history of the MHC’s property as the rhythm of summer break took hold. The Phase one archaeological work completed in July builds on Montclair State University’s (MSU) research in 2013 and 2014. Two goals motivated 2022’s investigation. 1) identify forgotten and potentially sensitive cultural resources or artifacts ahead of future improvement to the center's driveway and parking lot. And 2) gather data directing possible future archaeological research and collaboration between the MHC and MSU.

Archaeologists commonly refer to the excavation work completed in July as shovel test pits or STPs because of the work’s exploratory or "survey" nature. This type of work is rapid, often preceding detailed excavations, or where the objective is to quickly eliminate the possibility of sensitive cultural resources. Mapping the position of STPs requires the use of specialized computer software. For an adequate artifact sample, archaeologists typically space STPs five to ten meters a part, and when viewed as an aggregate, they form a grid. The MHC-PL (parking lot) project field crew used satellite-enabled "total stations," a device like what construction crews use in road or building development to translate points on a map to the real world, which in this case, was the parking lot of the MHC. The team dug 19 STPs, each about 50cm (20 inches) in diameter and anywhere 40 to 70cm (16 – 27 inches) deep. Material excavated from the STPs was filtered through a large wire screen. Anything looking culturally modified (meaning a human has interacted with it) was bagged and labeled for later lab analysis.

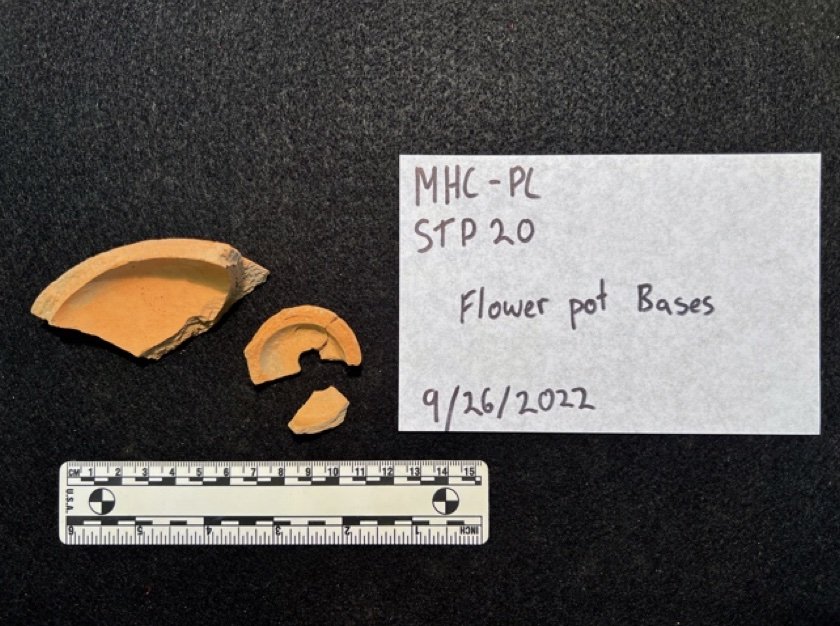

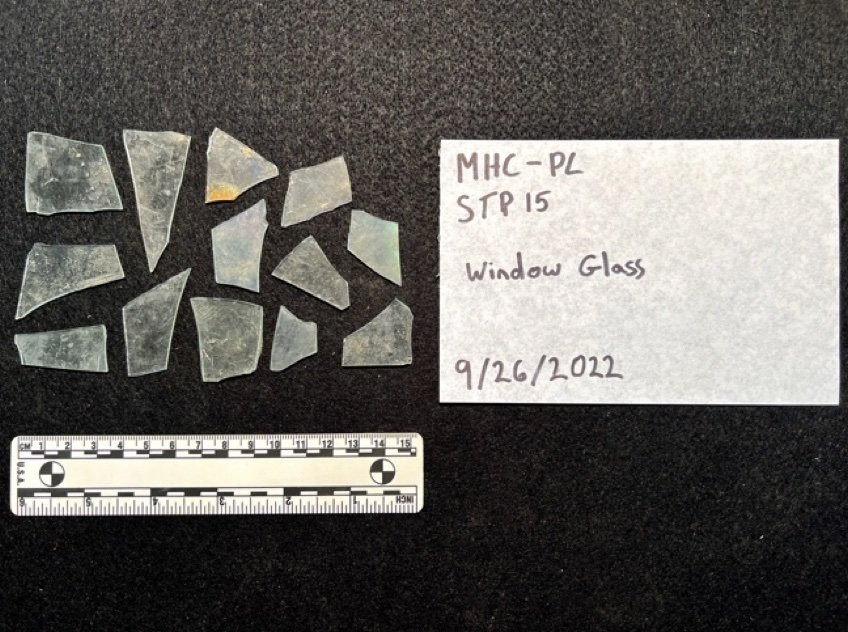

Most of the STPs dug in 2022 were on the south side of the center's property (110-116 Orange Road). Previous work explored the Clark house's front, side, and rear (108 Orange Road) and the location where the Montclair Community Gardens now grow. The team determined the area dug in 2022 was not previously excavated and was therefore embarking on a new set of questions and research paths. The artifacts recovered were not sensational finds. They did not hint at a garrison of Revolutionary soldiers or General Washington’s campsite. Instead, the objects spoke of everyday, routine life – evidence someone, probably not unlike us, lived and worked at a place people walk by each day. The team uncovered artifacts indicative of later Victorian to early 20th-century middle-class suburban life and industry. The artifact assemblage comprised brick-and-mortar fragments, coal, coal ash, window glass, and, most interestingly, a vast amount of flowerpot fragments.

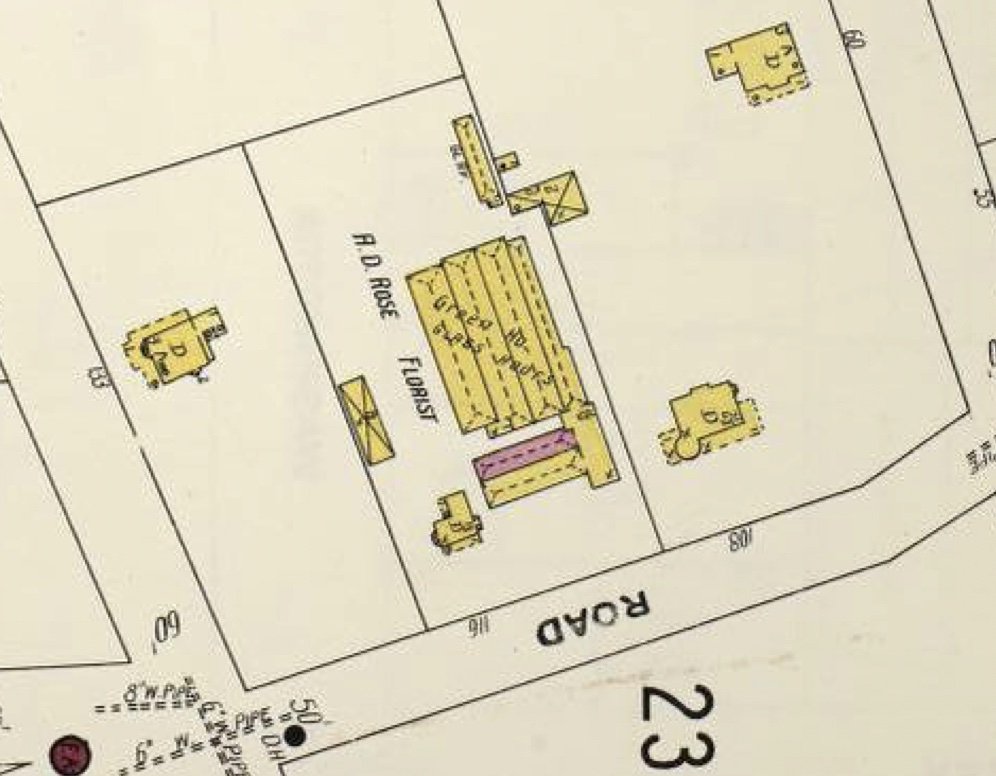

Typically, archaeologists expect to find a range of white ceramic earthenware and glass bottle sherds at residential sites.[2]However, 89% of all ceramics recovered in the MHC's parking lot and driveway were redware flowerpot sherds, and 82% of glass was the type commonly used in windowpanes. Primed with this information, the team consulted turn of the 20th-century historical maps and discovered a commercial greenhouse associated with the name A.D. Rose. These greenhouses and one residential building were located on the current site of the MHC’s Israel Crane house.

A.D. Rose Period

Figure 1. Photograph of Alister David Rose, printed in The American florist, 1908 as part of his obituary.

Alister David Rose was born on April 7, 1864, in Inverness, Scotland (Figure 1), and emigrated to the United States when he was 18.[3] Alister and his first wife, Sarah Rose (nee Trimnell), lived in Brooklyn, NY, with their three daughters Alice (born February 8, 1887), Lavenie (born February 7, 1890), and Mary "Polly" Rose (born May 11, 1893).[4] Sarah died in July 1894, less than a year after the Rose's youngest daughter was born. Following Sarah's death, Alister married Elizabeth D. Rose (nee Dewitt) in 1886, and the family moved to New Jersey. They ultimately settled in Montclair, NJ, and took over the greenhouse business at 116 Orange Road from Alexander Mitchie around 1899.

Figure 2. The Robinson map from 1890 showing the greenhouse layout before A.D. Rose took over the florist business from A. Mitchie.

Documentary evidence suggests Alister Rose was successful at his profession. At the new greenhouses, Rose "continued to do a thriving retail business, […] considerably [adding] to his glass area,"[5] an observation supported by late 19th century and early 20th century maps (figures 2 and 3). Rose was also a prominent member of the Montclair community and New York and New Jersey floral industry societies.[6] Census records show Rose employed at least two additional greenhouse hands as early as a year after taking over the business,[7] further proof of his success in Montclair.

Historical Sanborn fire maps from 1906 note a 66 x 14 feet brick structure, possibly with a glass roof. The team discovered three sets of features – a term describing unmovable, large objects – made from various brick styles that are potentially the remains of the brick structure indicated in the maps. These STPs, plus an additional test pit positioned in line with the three features, were almost void of the flat glass found in surrounding STPs. The combination of artifacts and historical maps indicates this building was a greenhouse heating system and partially fire resistant. Sanborn fire maps code a structure’s building material by identifying it with a different color. In the case of brick buildings, the color is typically purple (Figure 4).

Greenhouse operators at the end of the 19th century heated their structures in two ways. Either by circulating heat and smoke from a wood or coal-fired furnace through exhaust flues circumferencing the building. Or through piped hot water systems, also powered by wood or coal.[8] A heated greenhouse was an expensive investment. In 1885, smoke-flue heated greenhouses cost about $15 per running foot. Water-heating systems were the costliest, ranging between $20 - $30 per running foot.[9] The total linear feet of the Roses' greenhouses were approximately 1,400 feet. The cost for smoke flue heating would approximate $21,000, and for hot water heating, $28,000 - $42,000. These prices suggest that the 975 square feet (165 feet circumference) brick structure uncovered in features one, two, and three belonged to a flower hot house and did not heat all of the Roses’ greenhouses.

An Often-Overlooked Artifact

Figure 3. The Muller map from 1906 showing the expansion of the greenhouses at 110-116 Orange Road.

Figure 4. The 1907 Sanborn fire insurance map shows the position of a brick structure colored purple. This building was possibly a coal-fired hot house.

The production of machine-made flowerpots exploded following William Linton's invention of the pottery molding machine in 1861.[10] H. A. Hews Company of Weston and North Cambridge, Massachusetts, incorporated Linton’s invention into their production, resulting in a yearly output increase from 5000 flowerpots in 1861 to 700,000 in 1869.[11] Flowerpots are commonly found in assemblages from the late 19th and early 20th centuries; however, they are often overlooked[12] in favor of other ceramics. In the Phase One survey of the MHC's property, they are hard to ignore and represent 20% of the weight of all artifacts recovered (Figures 6 and 7). In comparison, white-bodied ceramics, typically associated with housewares, comprised only 0.46% of the total artifact weight.

Overlaying the artifact’s recovery position onto historical maps aligned to modern property boundaries shows the densest collection of flowerpots is located north of the hothouse where a roofed building stood (figure 5). Two hypotheses explain the artifact dispersion. Either this building was a storage structure for pots or shows the direction of demolition for an adjacent building. In the process of the greenhouses' destruction, the contents and building material could have been pushed north towards the driveway. Combined with the three brick features uncovered, the flowerpots direct potential archaeological work at the center.

Future systematic archaeological work should reveal more flowerpot sherds. This work includes excavating larger one-by-one meter "excavation units” or EUs. The data gathered from EUs will inform when the artifacts were deposited in the ground. The size of a flowerpot and the drain holes' position indicate what had grown in them.[13] Analysis of these future artifacts would complement the documentary record and provide supplementary information about the Roses’ operation. Alister Rose was known for his chrysanthemums. Additional data would help determine if his daughter Alice, who took over the business, continued growing the same flower type and adopted the same production methods.

Figure 5. In this “heat map,” each of the STPs excavated is represented by a red dot, and the green shaded areas, or clouds, signify the weight of flowerpot artifacts recovered in a STP. The heavier the shading, the denser the flowerpot sherds were in that STP.

The Rosary

Between 1906 and 1907, Alister Rose developed pneumonia. Although, as early as 1903, he suffered bouts of illness preventing him from working,[14] and he spent time in Florida recovering. Alister Rose died June 16, 1908. The property and business passed to his wife, Elizabeth, and their daughter, Alice, worked as the bookkeeper.[15] By 1912, the business changed its name to E.D. Rose, Florists, to reflect its new owner. In 1915, at 28 years old, Alice took the role of Florist with her mother,[16] and in 1916 became the sole proprietor, changing the business' name to The Rosary (Figure 9). The 1930 census shows Alice still running the florist, and it is assumed she did so until her death in November 1936.

Figure 9. An advert for "The Rosary" printed in the 1916 Montclair City Directory

We don't know where or if Alice trained in floriculture; she likely learned the trade from her mother and father. But her role as a business owner and florist was a growing trend in the mid-Atlantic region and possibly elsewhere. Five years before taking over the business, another female entrepreneur, Jane Bowne Haines, established in 1911 the Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women. This institution was the first of its kind in America, opening doors to women in the male-dominated horticulture/floriculture industry.[17] It's unknown if Alice attended this or any other school, but the parallel establishment of the school and Alice taking over the business indicate women's changing societal roles.

Details of the patriarchy’s machinations and the disproportion of power between the sexes are scattered throughout the documentary record. Evidence of this emerged as a recurring pattern while researching the history of the Roses and their business: after Alister's death in 1908, mention of the business under Elizabeth or Alice was non-existent – this is despite the fact Alice ran the business for over 20 years, much longer than her father. In a parallel account of the 20th-century floral industry overlooking women’s roles, an industry journal published a story of the "Rose Night" held in Orange, NJ, on June 17, 1904. The evening's featured, most acclaimed floral arrangement was awarded to an "amateur lady."[18] This unnamed individual, who the article emphasizes was a client of A.D. Rose, had her flowers presented by her brother, C. H. Wilmer. The anonymous lady's success had little to do with her brother and even less so did Alister Rose. Women struggled for recognition in the male-dominated industry. Any success was attributed to men. Evidence of the patriarchy is not unexpected; however, Alice's success – evident by the longevity of her business – flies against the prevailing wind of a male-dominated society and is perhaps one example of a slowly changing society starting with the women's suffrage movement.

On the heels of the Seneca Falls Convention on July 19-20, 1848, New Jersey narrowly passed a limited act protecting married women's property rights.[19] In 1855, the act was further strengthened with a bill focusing on women's property and parental custody rights.[20] Titled, An Act securing Equality of Rights to Women and Men, it stipulated that all real and personal property brought into the marriage and acquired afterward by wife or husband would be the separate property of the wife or husband respectively; that property of either husband or wife would be owned, used, or disposed of as his or her separate property and could not be liable for debts of the other.[21]

Sixty-one years passed between Alice taking over the florist business from her mother and the first legal changes affording women more rights and autonomy over their financial and personal futures. While the law provided women some rights, the needle of societal attitudes shifted slowly. Women were still considered inferior and often nudged into marriage and domestic roles in the early decades of the twentieth century, even if the term "housewife" was socially considered a pejorative term.[22] When a woman broke the mold of predestined domesticity, she was considered "aggressive, bold, unfeminine, threatening to men, and probably incapable of attracting a husband;"[23] women were punished for their success.

Alice G. Rose died November 29, 1936, at age 49, apparently unmarried and buried with her sister Levenie R. Syrett and her husband. Unless remaining single was intentional or a personal decision, her dedication to the business and resistance to conforming to society's pressures made Alice an example of what Gurko (1975) describes above. The creative name she gave the greenhouse, "The Rosary," implied her commitment to the greenhouse and florist business; she added personality to her work.

Gaining Meaning from Flowerpots

The greenhouses and business once occupying the MHC's land, where the historic Crane house now stands, seem inconsequential. The Rose's story isn't part of the grand native we tell ourselves to reinforce our national identity; General Washington probably didn't camp there. Nor is it the story of a prosperous family who, in part, built their success on the backs of enslaved labor. However, in Alice G. Rose's story, we see the hurdles and steps women took to liberate themselves from a society damning them if they acquiesced to the pressures demanding they follow the domestic life while also condemning them for setting out on their own.[24]

With more work, the archaeology of the Rose's greenhouses has the potential to develop a conversation about work and gender through the lens of an unlikely group of buildings in a quiet suburban setting in New Jersey. The history of the plot land now occupied by the Israel Crane house may seem inconsequential, and the Roses likely didn’t place much future historical value on their lives. However, Alice’s story, one of the thousands, is a stepping stone on the path of women’s rights. Her story contributes to the grand narrative of who we are and reminds us how far we’ve come.

Will Williams is a Ph.D. archaeology student at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York City, and an alumnus of Montclair State University. Please feel free to reach out with any questions to wwilliams@gradcenter.cuny.edu.

[1] “Nathaniel Crane House.” n.d. Montclair History Center. Accessed September 23, 2022. https://www.montclairhistory.org/nathaniel-crane-house-new.

[2] If you’re interested in the difference between “shard” and “sherd,” the explanation given to me was the former is flying bits of broken pottery or glass, and the latter is stationary and scattered or buried.

[3] American Florists Company, The American Florist: A Weekly Journal for the Trade (Chicago, 1908), 1129.

[4] National Archives and Records Administration, “Twelfth Census of The United States,” (Washington, D.C., 1900), 10; Findagrave.com. “Alice G Rose (1887-1936) - Find a Grave Memorial.” Accessed September 8, 2022, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/209115269/alice-g-rose.

[5] American Florists Company, The American Florist, 1130.

[6] Ibid., 1130.

[7] National Archives and Records Administration, “Twelfth Census,” 10.

[8] Peter Henderson, Gardening for Pleasure. A Guide to the Amateur in the Fruit, Vegetable, and Flower Garden, with Full Directions for the Greenhouse, Conservatory, and Window-Garden, (New York: Orange Judd Company, 1875), 90-95.

[9] Ibid., 93.

[10] Lathrop, Hazel H., “The Culture of Flowerpots” (University of Massachusetts, 2000), 58.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., iv.

[13] DeForest, “‘A Good Sized Pot’: Early 19th Century Planting Pots from Gore Place, Waltham, Massachusetts” (MA thesis., University of Massachusetts, 2010), 93.

[14] American Florists Company, The American Florist: A Weekly Journal for the Trade (Chicago, 1903), 757.

[15] The Price Lee & Co., Directory of Montclair, Bloomfield, Caldwell, Essex Fells, Glenridge and Verona (Including Cedar Grove)(Newark: The Price Lee & Co., 1912), 41 and 272.

[16] “New Jersey State Census, 1915” (Trenton, 1915), 8.

[17] Ambler Campus. “A History of Temple University Ambler,” April 1, 2020, https://ambler.temple.edu/arboretum/about/history/history-temple-university-ambler.

[18] American Florists Company, The American Florist: A Weekly Journal for the Trade (Chicago, 1904), 881.

[19] Dodyk, Delight W., “The Woman Suffrage Movement in New Jersey” (PhD diss., Rutgers, 1997), 46.

[20] Ibid., 50.

[21] Ibid., 50.

[22] Gurko, M., Ladies of Seneca Falls (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1975), 303.

[23] Ibid., 304.

[24] Ibid., 303-304.